The OECD has just launched its ‘How’s Life? – Measuring Well-being’ report for 2020. This is part of an OECD initiative to measure the development and overall quality of life of the inhabitants of its 36 member states, 21 of which are members of the EU.

The headline take away from the new report is that “Life has generally improved for many people in OECD countries over the past 10 years but inequalities persist and insecurity, despair and disconnection affect significant parts of the population”. This conclusion brings together the findings of research into a number of different areas such as income and wealth, health, social connections, civic engagement and, crucially, housing.

Regarding this latter topic, the OECD comments that “Housing provides shelter, safety, privacy and personal space. The area where people live also determines their access to many different services. Since 2010, there have been some improvements in OECD average housing conditions”.

However, it also notes that “The share of households living in overcrowded conditions in 2017 was 30% or higher in Mexico, Latvia and Poland, but 2% or less in Ireland and Japan. The share of poor households lacking access to basic sanitation in OECD countries ranges from over 25% to almost zero. OECD households spend, on average, around 21% of their disposable income on housing costs, but nearly 1 in 5 lower-income households spend more than 40%”. This goes some way to highlighting the vast disparities between countries and, indeed, populations within countries, when it comes to accessing quality, affordable housing.

Of course, the data being used by the OECD come with many caveats related to ‘quirks’ in or interpretations of the data in many countries. This is an issue which we at Housing Europe have already provided quite a lot of analysis on (see for example: ‘Are current measures of housing affordability fit for purpose?’ and ‘Trends in Housing Affordability’), so we will forgo further discussion here.

Overall, though, the OECD findings offer little in the way of the new information, and the scope of the analysis on housing is broadly in line with that of the more frequent EU Survey of Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) produced by Eurostat.

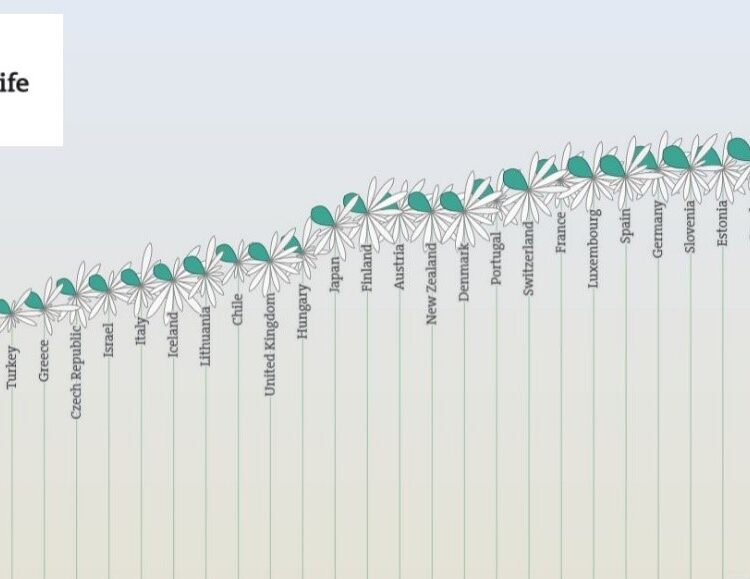

One interesting feature of the OECD figures, though, is the volume of data available at a regional level, which is something generally lacking from the EU-SILC. To this end, the OECD constructs a regional measure of housing ‘well-being’. This is a weighted index based on three measures; housing expenditure (housing costs to gross adjusted household income), percentage of population living in homes with basic facilities (e.g. flushing indoor toilet) and overcrowding (rooms per person). One clear caveat of the figures is that not all EU countries are members of the OECD and even amongst those which are, data is not always available.

Despite this, the large number of regions means presenting the region housing well-being figures graphically is virtually impossible. However, to give you just a flavour of the results, out of best possible score of 10, the Belgian regions of Flanders and Wallonia rank the highest amongst the sample, both scoring 7.8. They are closely followed by a large cohort of regions primarily from the United Kingdom and Spain.

The other end of the spectrum is dominated by countries in what is typically referred to as ‘Eastern Europe’, with Poland and Hungary seeing the highest concentration of countries adjudged to a have issues with housing related well-being. Again, there are issues with these figures, but they can at least provide us with a ‘sense’ of the scope of housing inequality which exists in Europe.

The OECD itself does a very good job of succinctly summarising the importance of housing, by stating that “Housing is essential to meet basic needs, such as shelter, but it is not just a question of four walls and a roof. Housing should offer a place to sleep and rest where people feel safe and have privacy and personal space; somewhere they can raise a family. All of these elements help make a house a home”. Thus, while we can argue over issues related to data collection and interpretation, these seem almost trivial when put up against the ‘bigger picture’ in relation to housing. It is a human right and basic need.

The OECD is due to publish a briefing on social housing in the European Union in the second half of this year (currently pencilled in for September/October). Let us all hope that it succeeds in communicating the importance of our sector in vindicating that human right and providing that basic need.