The study of affordability can be a tricky issue, but one thing that is generally accepted is that it is more of a problem in urban areas. In this latest article, our Research Coordinator, Dara Turnbull, suggests that based on the private rental market, very few major cities in Europe can claim to be ‘affordable’, and makes a plea for better data, and improvements in the monitoring of housing as part of the European Semester.

Measuring the ‘affordability’, or indeed ‘unaffordability’, of housing is fraught with difficulty. As we at Housing Europe discussed in a previous blog post, a judgement of the affordability of a home can depend to a large degree on the ‘measure’ used to assess such matters. For each different metric of housing affordability that exists, there are both strong and weak points, and housing experts could argue into the early hours of the morning about the perceived suitability of their own personal favourite affordability measure.

Having said that, as long as we acknowledge their inherent shortcomings, measures of affordability can still help to make real the struggles of households in a given region of country, and provide the impetus for policymakers to act. Therefore, to discount them completely would be a mistake.

Speaking of the lived experience of households, one issue that myself and my colleagues frequently grapple with is the apparent disconnect between commonly cited measures of affordability, such as those produced each year as part of Eurostat’s ‘Survey of Income and Living Conditions’ (SILC), and what we are hearing from housing providers in many countries with regard to a lack of affordable or adequate housing. Indeed, policymakers will often cite figures like those published as part of the SILC to defend their record on housing against such claims from other domestic stakeholders.

One of the possible issues is that while data like SILC deal with housing on a national scale, the worst affordability issues are usually localised. Thus, national averages could be masking meaningful regional dichotomies in terms of housing affordability. Although, to be fair, SILC does provide some insights on this. For example, in 2019 30.3% of those living in ‘cities’ in the EU lived in households spending 25% or more of their disposable income on housing, versus 19.2% of ‘rural’ dwellers[i]. However, without spending considerable time and effort digging around in the underlying SILC microdata from each country, more in-depth analysis of regional variations in affordability is difficult.

In lieu of a timely option from the likes of Eurostat, one commonly used source of local earnings data in Numbeo. It is a crowd-sourced price comparison resource, which allows users to provide information on various inputs such as the cost of living and net earnings (i.e. after tax) in a given location. These responses are then used to compile assessments of the costs for everyday essential good and services, proving a useful resource for those thinking of moving to a new city. The obvious caveat is that Numbeo relies on the so-called ‘wisdom of crowds’ in order to deliver accurate information. In other words, their data are only as good or as representative as the people supplying it. However, a quick sense check of their figures on net earnings show that they are generally ‘credible’, or at least not ‘incredible’. In the absence of other up-to-date data options, Numbeo provides a useful resource for matching rents to net earnings in European cities.

However, some options for analysis of sub-national affordability across Europe do still exist.

For example, when it comes to the private rental sector, the ‘International Service for Remuneration and Pensions’ (ISRP), working on behalf of various international bodies, including the EU, does produce comparative figures on rents in a number of European cities[ii]. This is done in order to help the institutions to adjust wages and expenses for staff to fit with variations in the cost of living in different locations.

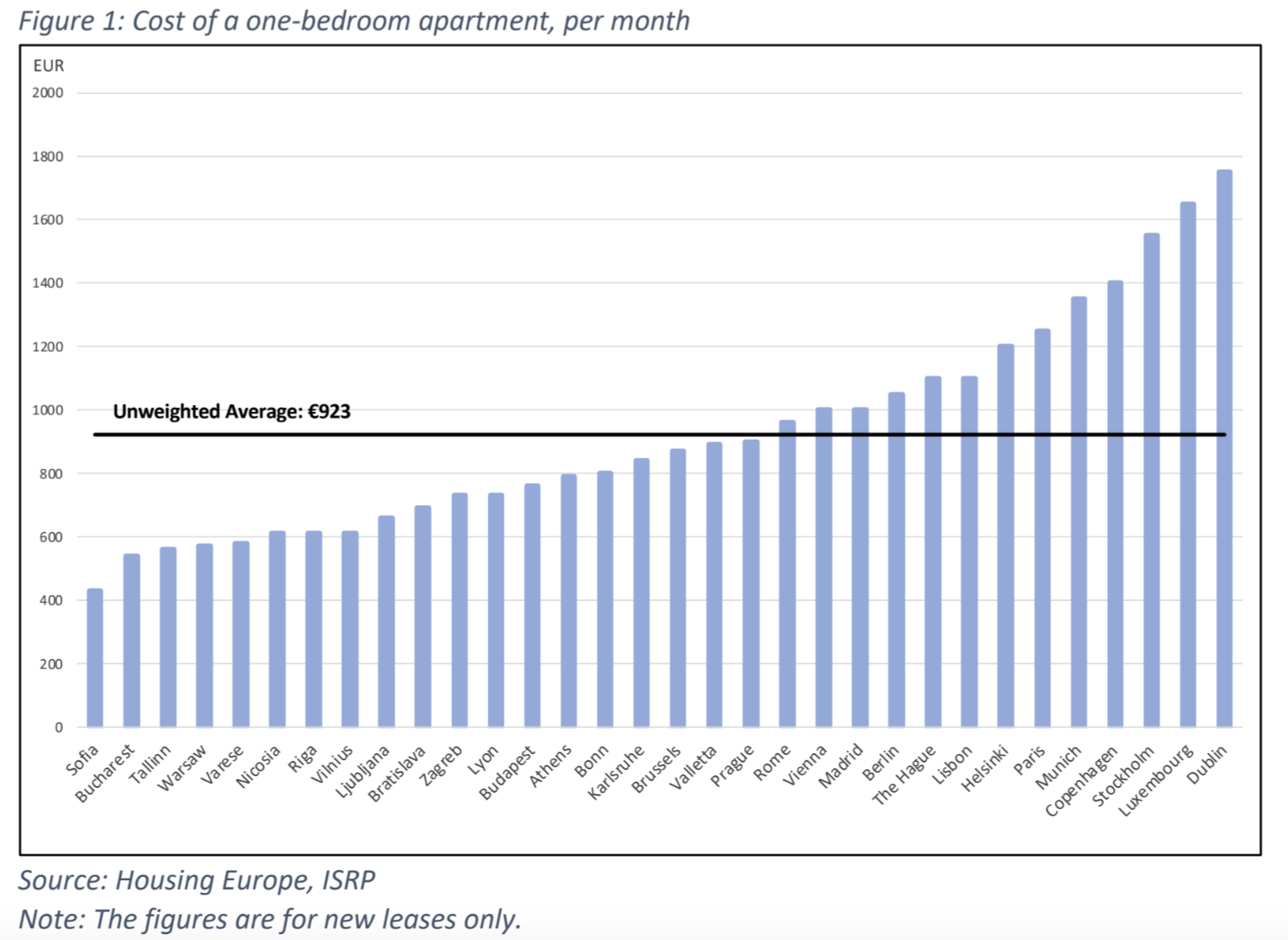

The most recent figures show that private rents vary significantly across the EU, which should come as a surprise to no one. Figure 1 (in the download section) looks at the average rent for the new lease of a reasonable quality one-bedroom apartment in a host of cities.

What the data show is that, generally speaking, housing in Western and Northern European cities is more expensive than in Eastern and Southern cities. Of course, the simple cost of a particular good or service does little to tell us about how ‘affordable’ we can assess it to be. Indeed, while rents vary quite a lot between locations, so too do average incomes. Thus, we need to go a step further in our analysis.

As discussed earlier, comparable ‘national’ level data are readily available from agencies like Eurostat. However, localised figures are harder to come by. This includes figures on incomes, without which assessing the affordability of rental housing in European cities will not be possible.

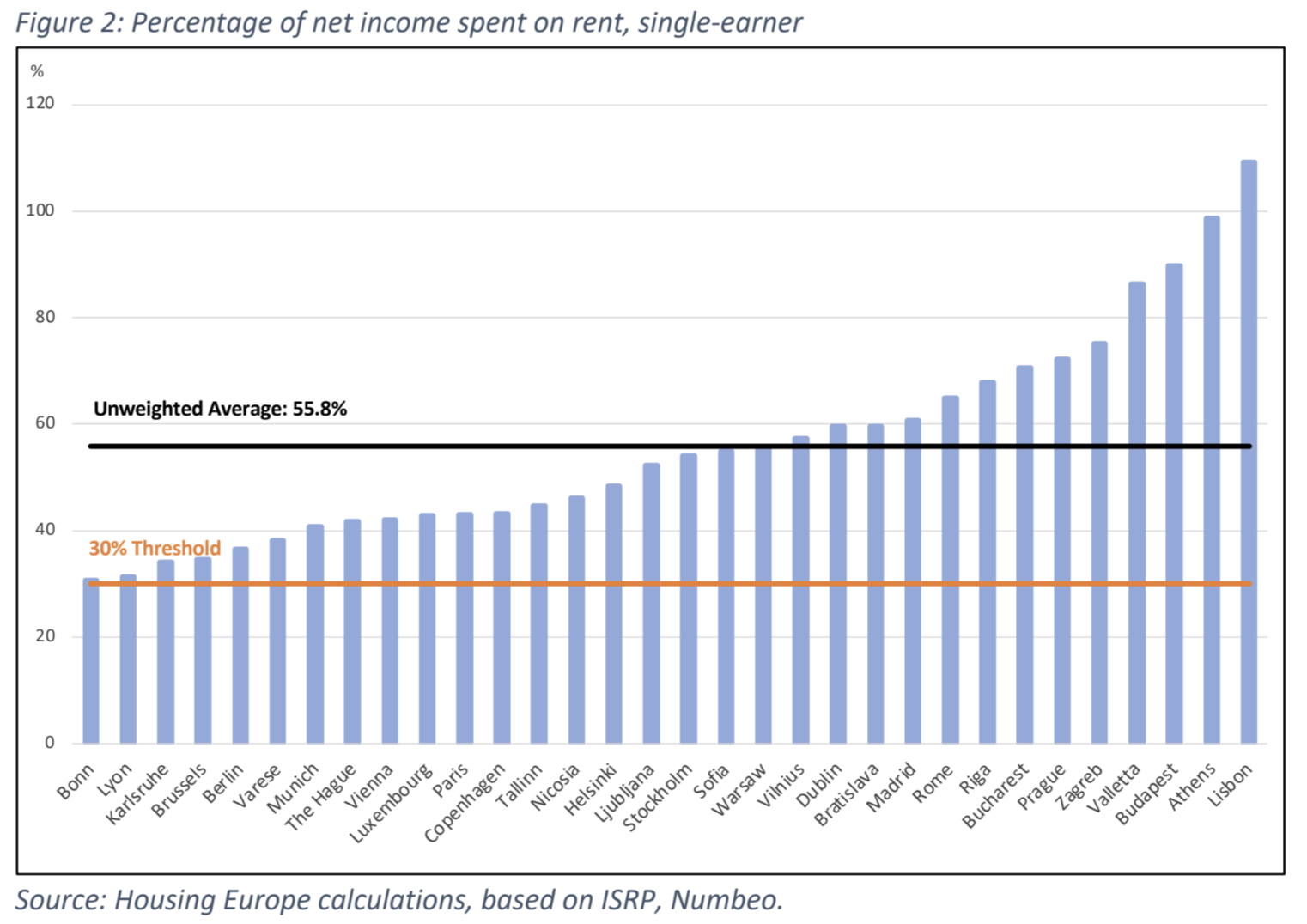

If we look first at the case of a single adult, with the average net reported earnings in each city, paying the average rent for a newly leased one-bedroom apartment, then cities with the highest reported rents do not necessarily have the most severe affordability issues. For example, the least affordable city in Figure 2, Lisbon, where the average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment is more than 100% of the reported average net monthly income, is only the eight most expensive city rent reported by the ISRP. The second and third least affordable cities, at least based on our calculations, Athens and Budapest, have below average rents, as shown in Figure 1. Thus, relatively low rents in a city are not necessarily indicative of affordability, or vice versa.

Taking a step back for a second, what is striking about Figure 2 is that for a single person, with the average net income, in none of the cities in the sample does the rent fall below 30% of their take-home pay. Indeed, the average rent as a percentage of net income in the sample is 56%! While we must be careful not to come to any overdrawn conclusions, given the nature of the underlying data being used, it still points towards a worrying situation for many households. Not least because we are looking here at the average income, one can only imagine the situation faced by a low-income single earner in these cities.

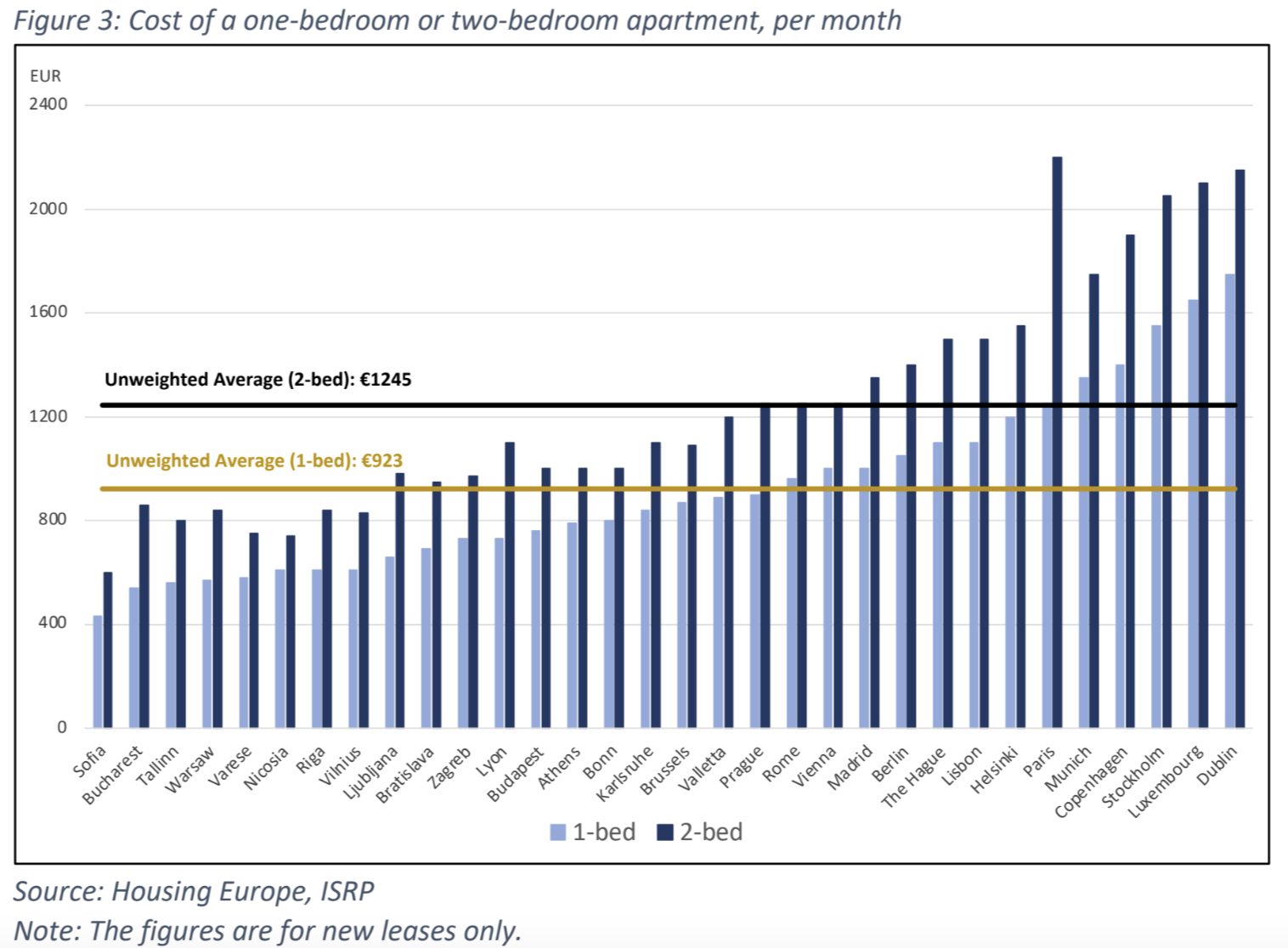

If we move one step up on the ladder, what is the situation for a hypothetical two-income household; for example a young couple? Firstly, we must consider what sort of home they live in. While a one-bedroom apartment is a feasible prosect for many, assuming they have no children, a desire for more space is natural. This is especially the case in the age of increased home-working, where a second bedroom can double as a home-office, or recreation space. Thus, we will consider the affordability of both a one- and two-bedroom apartment. As shown in Figure 3, there are certainly some economies of scale to scaling up. The difference in the rent for a one-bedroom apartment is not so different from the rent for a two-bedroom option, in most cases. Paris clearly stands out in this regard, where there is a significant premium to be paid for having a second bedroom.

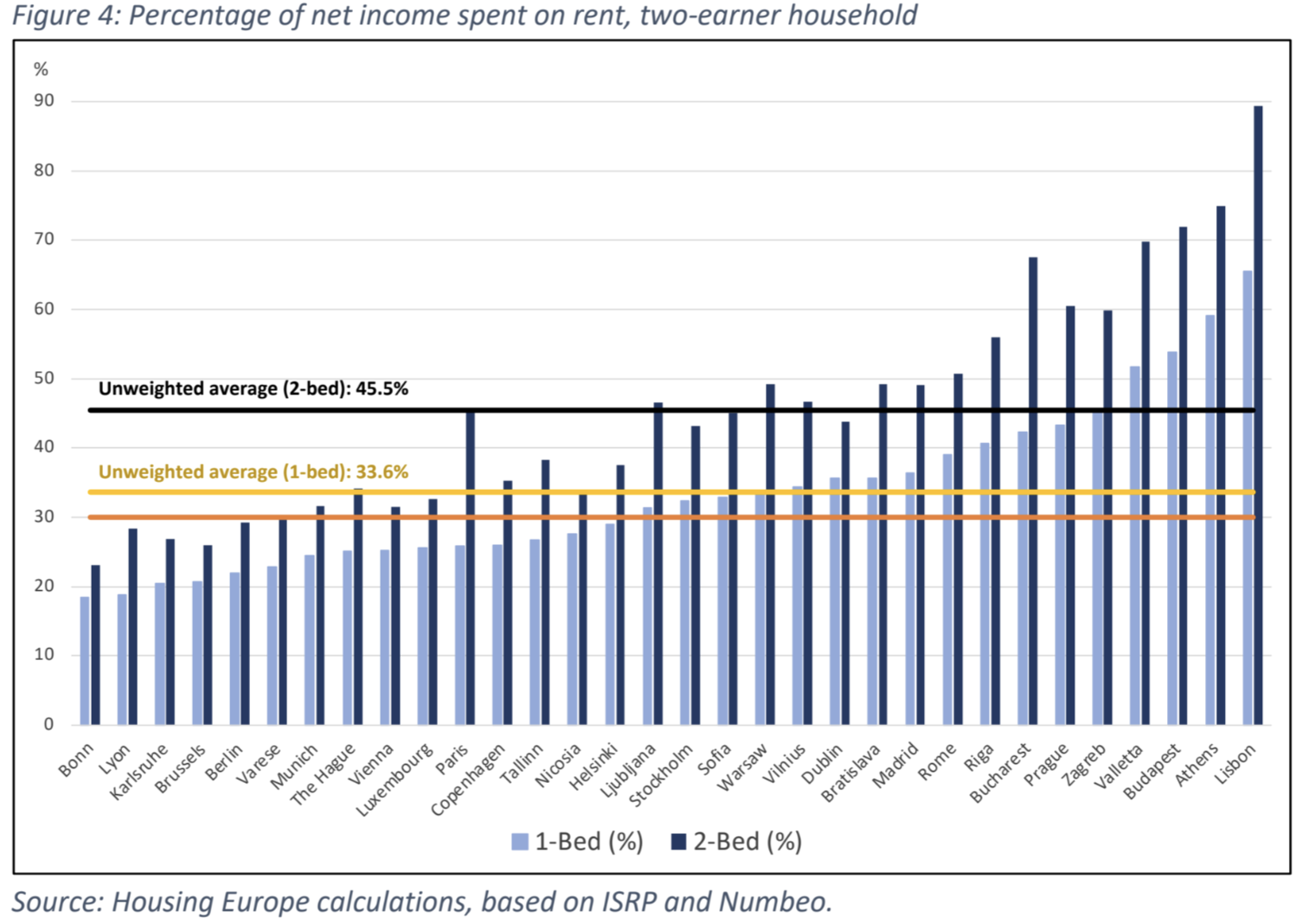

Figure 4 (in the download section below) outlines the relationship between private rental and net earnings for our hypothetical two-earner couple. In this case, we assume that one earner is at the average net income, while the second is at two-thirds of the average. Thus, the couple are still not a ‘low-income’ household by local standards.

What we can see is that when a second income earner is added, the affordability situation improves. Indeed, while no city fell below the 30% threshold for a single-earner renting a one-bedroom apartment, a number of cities meet this affordability standard for the two-earner household.

However, the differences between cities remains stark. While the couple will pay less than 20% of their net income for a one-bedroom apartment in Bonn or Lyon, in Lisbon or Athens they are close to, or even above, the 60% mark. When it comes to a two-bedroom property, only a small fraction of cities fall below the 30% level of required net income. Again, we must emphasise that the two-income household in this scenario is not low-income, and yet privately renting a home is clearly an issue for them in most instances. Thus, those with less means will feel the economic strain linked to housing themselves more acutely, or else will be left in the situation that living in the city is simply not an option.

This can see them forced to give up employment or educational opportunities, strain family or community ties, and reinforce the so-called ‘insider’ versus ‘outsider’ problem, by which those not already living in a city are prevented from accessing the various opportunities that may be available there. This is bad not only for the individual households concerned, but also for the wider society. Indeed, as noted by the OECD in a recent Working Paper: “Moving matters. The ease of moving residence geographically has efficiency implications because it affects the job-matching process: low rates of residential mobility can be an obstacle to labour adjustment, making labour markets less efficient, with adverse effects on overall economic performance”[iii].

At the same time, the OECD also notes that “[t]he ease of moving residence geographically also has wellbeing and equity implications, because it affects individual and family opportunities to climb the socioeconomic ladder through various channels; for instance, by getting higher earnings via moving to denser, more productive areas with higher paying jobs, by getting access to better education and training opportunities, and also to better neighbourhoods, especially for children and young people coming from disadvantaged backgrounds”. Thus, the current housing situation in many cities is not conducive to social mobility.

That is, of course, unless a more affordable alternative to the private rental sector is available, such as social or public housing. While many countries in Europe have quite broad eligibility criteria for access to such housing, social providers still provide housing for low- and moderate-income households in Europe to a disproportionate degree. Thus, when the supply of such housing is sufficient to provide a more affordable alternative to the private market, these households can be supported to overcome affordability hurdles in their chosen city.

Although, as Housing Europe outlined in its recent ‘State of Housing in Europe – 2021’ report, a lack of social and affordable housing is a significant issue in many parts of the continent. For example, we reported an unmet need for an additional 1.6 million affordable homes in England, at least 225,000 in Germany, and 110,000 in the Netherlands, to name but a few. In the absence of sufficient social housing, many households find themselves stuck in unsuitable housing situations in order to put a roof over their heads. This can include everything from living in accommodation that is overcrowded, to being forced to live far away from work or education, leading to long daily commutes. In the more severe cases, homelessness is the unavoidable result of such housing scarcity.

To conclude, what this short article highlights is the need for more robust analysis of affordability issues ‘within’ countries, and not just ‘between’ them. This can help us to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by many households in Europe today. In the absence of such analysis, it is likely that sufficient resources will not be made available to adequately and effectively deal with housing affordability issues. This includes, but is not limited to, a lack of available social and affordable housing. The negative social consequences of this runs the full spectrum from stress and ill-health, to homelessness, or worse.

In conclusion

The need for better and sub-national data on issues related to housing has been a constant refrain from those involved in our sector, and many others for years now. Indeed, as was written in the Action Plan of the Housing Partnership, under the auspices of the work of the Urban Agenda for the EU, back in 2018: “National housing markets are increasingly fragmented, and their segmentation continues. This process poses important questions about the future of territorial development and cohesion, among other vital issues. Unfortunately, data − especially spatial data mapping housing prices (rent and purchase) on the subnational levels − is lacking at the EU level. Instead, housing prices are available and monitored only at the member-state level”. In addition, the Action Plan noted that “recommendations on housing are made from the perspective of possible macroeconomic imbalances based on national figures … policies that did not take into account local and regional peculiarities”.

At the same time, the Action Plan is also critical of the monitoring of housing as part of the European Semester process, which represents a missed opportunity to provide comparable and timely insights on this important issue. It makes a number of recommendations for reform, which Housing Europe full endorses:

Recommendation 1

The Housing Partnership concludes that more work needs to be done to account for diverse affordable housing tenures along the housing continuum in addition to/or by refining the HPI indicator in the Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure of the European Semester. This is in order to ensure that the semester process and the CSRs take into consideration all housing tenures, including the rental market in the social/public, cooperative and private sector, rather than only one of them.

Recommendation 2

The Housing Partnership concludes that, in order to improve the analytical basis of the housing assessment in the country reports and the CSRs, a thorough and complete monitoring of all housing tenures along the housing continuum, as well as inter alia research into the geographical differentiation between low-demand areas and heated housing markets, must be included. The situation in cities and urban areas should be monitored specifically, as critical developments leading to potential financial crises start here.

Recommendation 3

Develop an indicator on social and affordable housing in the Social Scoreboard by introducing a revised definition of housing cost overburden in combination with other indicators, for example as rates of eviction and poverty rates that better take into account the realities of the socio-economic situation of EU citizens. The Housing Partnership recommends that the reference threshold of total housing costs should not be higher than 25% of the disposable income of a household, when calculating the housing overburden rate. Member States should develop the relevant national, regional and local policies and strategies that shape the conditions to achieve this goal in line with the principle of subsidiarity.

Recommendation 4

In order to strengthen investment in the short term and within the existing framework, a more active use of the investment clause in the European Semester for financing affordable housing should be envisaged. In addition, investment programmes for affordable housing should be interpreted as structural reforms.

Download the blog post below.

[i] Based on ilc_lvho29

[ii] See : https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/civil-servants-remuneration/estate-agency-rent-surveys

[iii] OECD (2020). Should I stay or should I go? Housing and residential mobility across OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1626. Paris: The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.